In the Greenough Room: George Greenough

“George was the club’s only non-surfing member. He never stood up on his board, he never cut or even combed his hair, and always was a bit disheveled, but he was a very inventive guy, and certainly a great waterman.””

"When I took my designs to Australia, the reaction was huge, in fact bigger than here. All the Australian surfers immediately started making and riding shortboards, and then the movement came to the States."

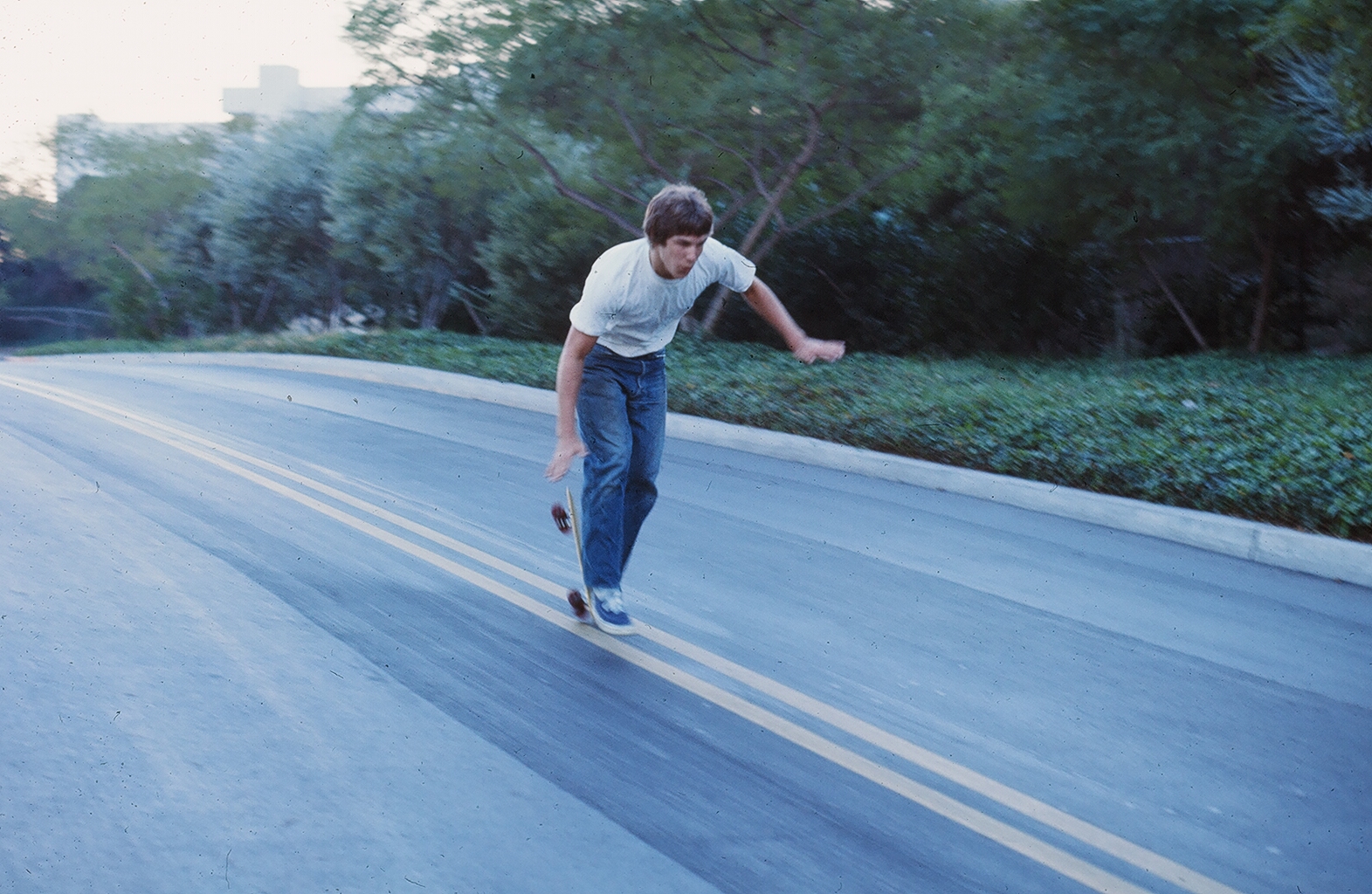

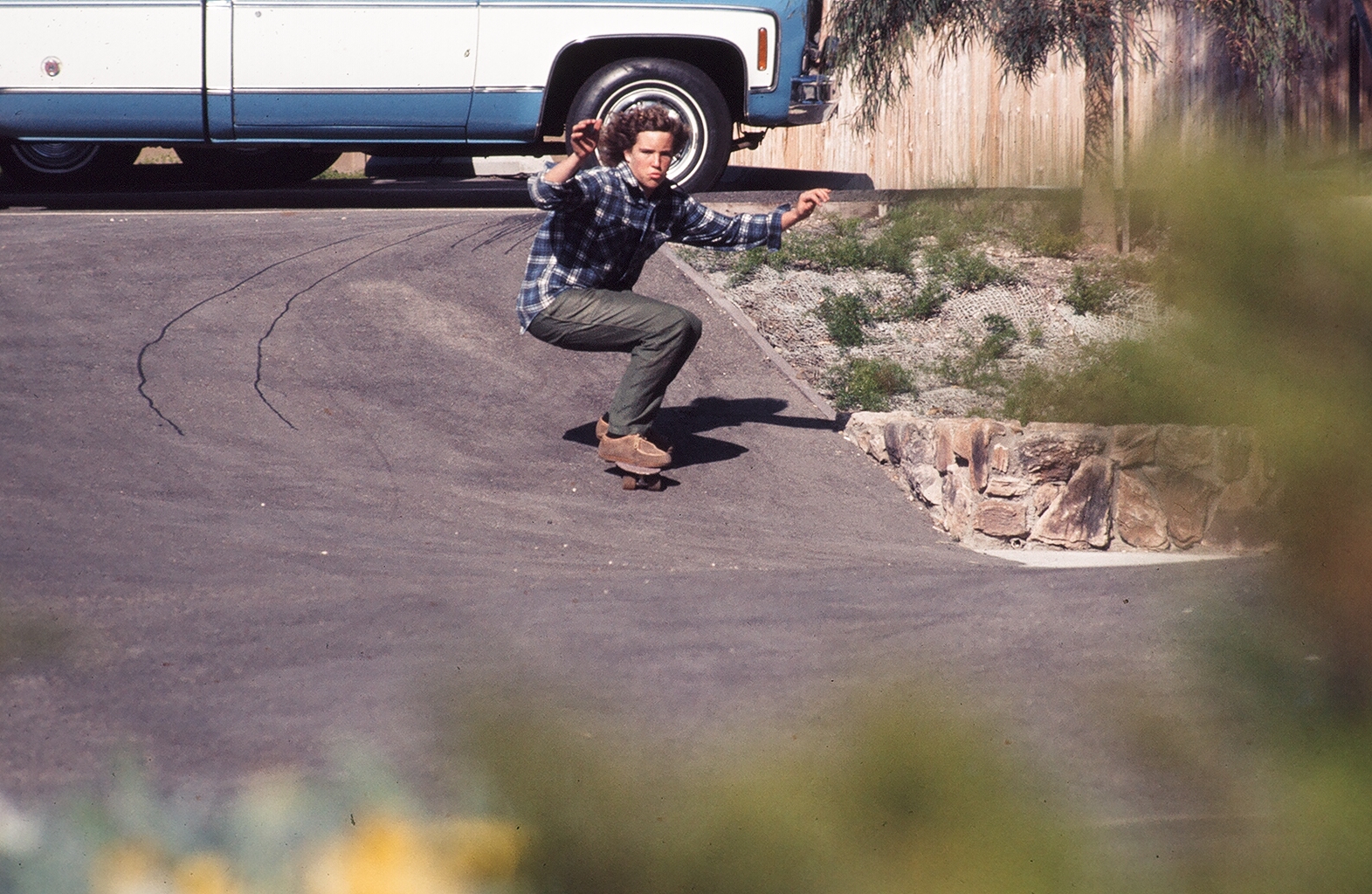

If George Greenough's feet could talk, they'd tell stories of innovation, invention, travel, and trailblazing. They've only been confined by shoes but a few times in their 75-year lifetime, so they've seen everything Greenough's seen. They started their journey in Santa Barbara, where George first fell in love with all things ocean.

I had heard his name long before I came to know what a surf icon George Greenough truly was. The revolutionary surfboard designer, gifted filmmaker, and all-around renaissance eccentric pioneered many of his famous innovations in the waters off Hammond's Beach near his parents' Montecito estate. Growing up during the '50s and '60s, the golden days of Santa Barbara surfing, Greenough embraced the laid-back lifestyle while pursuing, with an obsessional focus, any method, however strange, that would enhance his experience of the waves. Eventually his experiments spawned a surfboard design movement that has turned Greenough into a living legend.

As an early member of the Santa Barbara County Surf Club, Greenough was able to test his radical designs in the challenging waves of Hollister Ranch, then still owned by the Hollister family. Except for this privileged handful of Santa Barbara surfers, no one was allowed access to the beach, which was often patrolled by gun-toting cowboys.

Many other surf icons came out of that early club, but probably not one was as unique as Greenough.

“I surf with dolphins a lot, and they are always in the water.”

Greenough is widely credited with convincing an entire generation to abandon their longboards and join the shortboard revolution. Now at 74, Greenough continues to live a reclusive and eccentric life - in three decades he's never held a job and has rarely worn shoes.

The Designer

By his early teens, Greenough (pronounced green·o) himself had already abandoned traditional surfing in place of kneeboarding and soft mat-riding, two sports few others were participating in at that time. "I really never liked the longboard, it had no flexibility or spontaneity," recalled Greenough from his home near Byron Bay, Australia. "You couldn't really do anything with it, and the boards were heavy and hard to handle. So, I made what I needed to help me fit tighter into the pocket of the wave."

Greenough's parents' expansive Romero Canyon home and lawns provided him with the space — as well as financial and family support — to fulfill his creative drive, and to produce a board to fit his unique style. His experimentation and love affair with the water led him to create boards that challenged riders and were, in fact, more fun to ride. During this time, most surfers were using cumbersome longboards (9'6" in length, weighing 25 pounds), which lacked flexibility and allowed a surfer to do little more than ride straight down the face of a wave.

While in wood shop at Santa Barbara High School, Greenough completed a rough kneeboard design made from balsa wood, launching the "spoon" kneeboard. "I needed a project for wood shop, and everyone else was making birdhouses and such," said Greenough. "I needed a board that would fit deeper into the wave's tube, so I created the spoon. It was a great project, and the teacher gave me an A."

The spoon was a short board — just under 5 feet and weighing only 6 pounds — made of an all-fiberglass kneeling area with foam on the nose and sides. "A few versions later, I shaped a spoon with a fin design that I borrowed from a tuna. It made the board easy to maneuver in the water," added Greenough.

For surfers, the difference between the spoon and the longboard was immediate. Both the spoon and Greenough's ultra-modern fin design were groundbreaking movements in the evolution of surfing. With the spoon's intuitive steering attributes, and some good surf, Greenough was not only able to turn, but to completely change direction with his board, float on the whitewater, and perform other maneuvers considered progressive - maneuvers that had never before been done.

Eventually, Greenough's fins moved from home experiment to retail item when Morey-Pope Surfboards, a San Diego shop spearheaded by Boogie Board creator Tom Morey, started manufacturing Greenough's fins. The most popular design, and Greenough's favorite, was the Greenough Stage IV, shaped for power turning, and now readily available to every surfer, not just Greenough's friends.

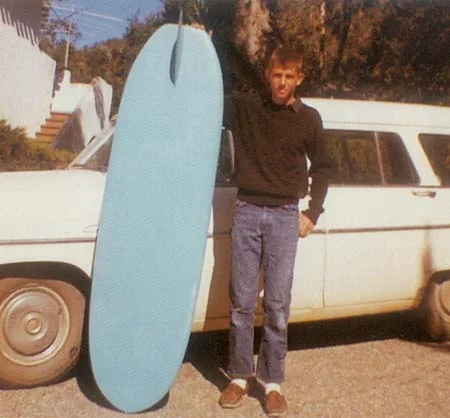

In 1962 Greenough shaped the Baby, a 7¢8≤ board designed for shortboard surfing. It boasted technical attributes never before seen in board design: It was short, its deck was slightly curved, its sides - or rails - were thick and round, and it had one of Greenough's innovative fins, all of which gave it more responsiveness and maneuverability. Now surfers could carve up the face of a wave standing on a surfboard rather than kneeling on a spoon or other kneeboard. What added to the board's distinctiveness was that Greenough borrowed a pint of color from fellow Surf Club member and surfboard shaping genius Renny Yater, and tinted his Baby the color of the sky. "I hardly ever rode that board," Greenough said. "My friends loved it, so they'd take it out at Rincon and have a lot of fun."

“I needed a project for wood shop, and everyone else was making birdhouses and such. I needed a board that would fit deeper into the wave’s tube, so I created the spoon. It was a great project, and the teacher gave me an A.”

By the time the 1966 World Surfing Championship rolled around, the event's champion, Australian Nat Young, won the contest by riding his winning wave on a surfboard featuring a Greenough-shaped fin, and later credited Greenough for his success.

"When I took my designs to Australia, the reaction was huge, in fact bigger than here," said Greenough. "All the Australian surfers immediately started making and riding shortboards, and then the movement came to the States."

While others in Santa Barbara and Australia, where Greenough now calls home, rode his boards, he continued his passion and devotion to kneeboarding, leading the kneeboard craze in the late 1960s and 1970s. Still, what really turns on Greenough is a truly obscure obsession - inflatable mat-riding.

"I love mat-riding. The mats are very easy to transport, and you don't need high-quality surf to catch waves and have fun. And with mats, it's all about the fun," said Greenough. "The mats let you get closer to a wave than a board does. You're laying flat, right on the water, and you can feel every movement of the wave."

Greenough's experimentation and design didn't stop at surfboards and kneeboards. There was also his homemade boat, The Coupe de Ville, fashioned from fiberglass and the hull of a 16-foot Boston Whaler. Its crowning glory: a rear window lifted from a 1957 Plymouth that functioned as its windshield.

"The Coupe was a great boat to take out to the [Channel] islands," said Greenough. "Hardly anyone went out there at that time, but we'd go out there as often as we could." The boat was featured in a documentary (eponymously titled The Coupe) Greenough made about a trip to Santa Rosa Island on what appears to be a quintessential California day: glassy waters, head-high surf, abalone hunting, and wreck scavenging.

The Filmmaker

Greenough also broke boundaries in surf filmmaking. His only full-length feature film, The Innermost Limits of Pure Fun (which opened in 1969 at the Lobero Theatre), offers a nostalgic look at Santa Barbara during the late 1960s with familiar scenes from Montecito to the Channel Islands, including Greenough shaping boards in his parents' backyard. But the film's surf sequences laid the groundwork for generations of surf filmmakers. To capture tube shots from in the water, Greenough outfitted himself with a shoulder-mounted waterproof camera that weighed 28 pounds, donned a diver's full-length wetsuit, and waited patiently. He had begun developing this cinematic technique for still photography several years earlier when he was the first person to shoot a surfer inside the wave's tube.

In Echoes, a 23-minute short filmed in 1972, Greenough fine-tuned his water photography skills by primarily focusing on underwater "in-tube" shots. His 1971 short film Rubber Duck Riders was his tribute to mat-riders, by then a vanishing sport. His expert filmmaking and intuitive eye landed him several assignments on feature films including Big Wednesday and Rip Girls. In 1973, Greenough himself was a subject of documentary short Crystal Voyager, filmed entirely in Santa Barbara to record the making of The Coupe.

Today Greenough can be found where I found him: at his home on Australia's east coast. His filmmaking, surfing, and beach lifestyle keep him busy, with little time for pontificating about the past. "I'm busy with two more films that document the making of Dolphin Glide, and I have to get into the water every day," said Greenough. "But someday, I need to get back to Santa Barbara. The surf is crowded there, but I have a lot of friends that I'd love to see. Y'know sometimes I miss the place."

Bob Marley, 1976

“In 1976 Bob Marley & The Wailers dropped in on the Santa Barbara Bowl. It was part of The Rastaman Vibration tour which began at the Tower Theater in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, on April 23, 1976, and ended in Manchester, England, on June 27, 1976. Along the way, they stopped in Santa Barbara and played to a sold-out crowd. ”

These, never before published photos, are from the collection of Randy Erikison, staff photographer of a generation of music lovers and a devoted Marley fan.

He's captured the essence, not only of a laid-back concert scene with fans hanging out on stage, but of the Marley known and loved the world over.

Marley played with his full line-up: Bob Marley, vocals, rhythm guitar; Aston Barrett, bass; Carlton Barrett, drums; Donald Kinsey, lead guitar; Earl "Chinna" Smith, lead guitar; Tyrone Downie, keyboards; Alvin Patterson, percussion; The I-Threes, backing vocals.

The Marley strut as seen on the 1976 version of the Santa Barbara Bowl stage.

The amazing I Three, popularly called I Threes, Rita Marley, Judy Mowatt and Marcia Griffiths. Their band name is a spin on the Rastafarian ‘I and I’ concept.

First Surfs & Best Waves: The Legend of Mando's Mary

A bonfire was lit, and out of one of the Malibu grass shacks came the legendary ‘surfer girls’…finally to the most applause, Shirley from Temple City, Gidget and Mando’s Mary.

When I met Mary Monks she was 77 and still driving out to Ventura’s California Street with her husband Bob to check the waves. Mary didn't ride a surfboard until 1953, when a trip to Hawaii inspired her to take surfing lessons from an instructor on Waikiki Beach — she was 36 years old! She returned from the trip a changed woman, and within a few months purchased her first surfboard— a Greg Noll balsa and foam.

Throughout her life, she primarily surfed where she lived— the northern coastline of Ventura County, California, between Ventura Overhead and Rincon. With her first board, Mary started surfing at Mando’s (in Ventura County), and then Rincon. Although “The Rock,” located at the Los Angeles-Ventura county line remained one of her favorite surf spots.

During this early time, from the mid- to late-1950s, Mary was living with Bob in a small cottage six miles north of Ventura. The cottage was owned by her mother, whose house sat on the beach—in front of the cottage—and looked out towards Santa Cruz Island.

It was Rincon where I caught my all-time greatest wave on my little splinter. Kenny Kessin said it was definitely fifteen feet.

When Mary, and later her friends, started surfing the beach break in front of the house, the break became known as “Mary’s.” Technically a part of Pitas Point, one of the longest points in Southern California, Mary's produces fast, well-shaped rights on strong winter swells.

In 1955, Jack Cantrell, a longtime Ventura County surfer, gave Mary the nickname “Mando’s Mary”— and it stuck. Nat Young, in his book, The History of Surfing, wrote about one memorable beach party where the who’s who of surfing were present. Mary included: “A bonfire was lit, and out of one of the Malibu grass shacks came the legendary ‘surfer girls’…finally to the most applause, Shirley from Temple City, Gidget and Mando’s Mary.”

After her Greg Noll board, Mary owned only two other boards, a Velzy Pig, and a Velzy/Jacobs splash-coated foam board. The latter hung in the rafters of her garage.

When I interviewed Mary, in the late Fall of 1995 and in the spring of 1996, she spoke about surfing and the surf culture along the northern Ventura County coastline. We leafed through her photos, looked at her first booties—Japanese two-toed slippers with rubber affixed to the bottoms—and read a hand-scribbled poem about her surf break. Her story is a unique trip down surfing's memory lane as told by a woman whose uncanny memory takes us through her first surfs, her first boards, her best waves…

In the beginning...

I started living at Mary’s in 1946, when Bob and I got married, the first time. My mother lived in the front of Mary’s, our little place was in the back, on the right. But we were in my mother’s house a lot. It was built on the sand, a cute little house. It was eventually torn down and replaced with fancy homes.

At Mary’s we first rode mats. This is, of course, before I ever surfed. They were canvas mats full of air, they weren't too big. We'd lay on the mat, paddle, and then the wave and white water would pick us up and take us in. That was in 1947 or '48. You could ride white water really good with those old mats. That was at Mary’s nobody surfed there then. It wasn't called Mary’s then.

Mary’s first surf…

My sister and I went to Hawaii in 1953 and I got the surfing bug. While there, I had a guy help me leant to surf. He wasn’t one of best, but he was OK. I had to pay for the lessons, but it didn't cost much. He would stand on a rock out there at Waikiki Beach and give me a shove. I'd go ten feet and fall off, then I'd go ten feet and fall off. I just couldn't get the knack of it. But one day I did do better. I was using a hollow board, which filled with water and got heavy, but you could take the plug out and drain it. Since that time I really haven’t had any desire to go back [to Hawaii], we have better surf here. Unless you go 'round to the other side of the island, to the places where you 'bout get killed.

Anyway, I came back, and got a board. I believe my Christmas Club money was $150. With that $150 I bought the three boards from Greg Noll: our son Larry's, Bob's and mine. That was $I50 for three boards, not for each board! My son conned me out of the board that was for me, he said the other would be better for me. So I ended with a little splinter for my first board.

So, I had three boards. My "splinter” was the first. My second board was from Velzy and Jacobs. It was what you call a "pig" board. And my last board, which is in the garage, I got from Velzy, just about the time he and Jacobs were splitting up. It was so cruddily put together they had to splash-coat it—the foam was imperfect. But I used that board more that the first two and really liked it.

Anyway, we got our first boards in November of 1955 and didn't surf until June of 1956, when we went up to Rincon. It was so big that day—I had never even been on a board or anything. We watch those guys surf, and it was so big we turned around and went back home. We didn’t know how to surf at all. What a dumb thing to do, to think you can surf Rincon when it is that big, when you don't know how to surf! But we were all jazzed up and wanted to surf. So we went back to Mando's, and started surfing there.

It was called Mando’s because there used to be a restaurant called Mando’s, but it burned down. Mando’s was smaller than Rincon and really not much of a challenge, but we surfed it. Then, when we were better, the next year maybe, we went back to Rincon and surfed there. But we still surfed at Mando's quite a bit. That’s when Jack Cantrell nicknamed me "Mando’s Mary.”

Mando’s would sometimes get pretty big. The waves were very, very slow, and you can get a pretty long ride there. Everybody liked it there, well not everybody, but a lot of them did because of the nice waves. And there were no leashes then, so I spent half my time paddling to get my board. My boards would always go clear to the shore.

Mary’s…

Y’know, the grass is always greener on the other side of the hill. Well, we surfed California Street, we surfed Rincon, we surfed down south, San Onofre…. but not Mary’s.

We didn't start surfing there until the other spots got crowded, and some of the guys surfed at Father John's, but there was nothing but big rocks there. Mary’s is on a little point. It is not a huge wave, but a nice, fast wave. It takes a west swell. From Mary’s down you can a long, long ride—clear down to where Jack [Cantrell] lives [at Faria Beach]. We’d ride down and walk back, I’d mostly paddle back, they thought I was crazy—for paddling that is.

Mary’s usually didn’t get really huge. An eight-foot day would be a good day there. It didn’t get big like Rincon, where I once caught a 15-foot wave. But Mary’s was so handy, so close that it ended up being my favorite surf spot!

Wool sweaters and wetsuits…

The water was very cold. For three years, I would just wear a wool sweater. It didn’t get too heavy in the water, but you had to get the right weave. It had to be a tight weave. You really had to be careful what you bought. Bob used to get bad sweaters and once his sweater was so heavy he almost drowned. We used to go to the Salvation Army and scrounge around for lamb’s wool—that was good wool. So I would just wear a lab’s wool sweater and my bathing suit and that was it! We roughed it.

Though the water was cold, I usually ran out of muscle before I got too cold. In the beginning, we used to surf with nothing, no wetsuits, no booties, no leashes. I think the third or fourth year I was surfing, I got a wetsuit. But it wasn’t like they have now. It was just short-sleeved and you would strap it up between your legs. We had to go clear down to Redondo Beach to get my wetsuit. I can’t remember the name of the shop, but it was a real popular shop. The year before, Bob and my son got one that I think they had to glue together. It was the same principle as mine, but they had to glue it together. Bob go his suit in Santa Barbara from this guy who was making them. Anyway, I had two wetsuits. My first, and then the second was a regular one, like the kind the kids wear now. Of course, we never had a lot of money, but we always managed to squeeze out money for surf gear.

Bob would sometimes cut his pants up to make shorts and stuff, because there weren’t too many shorts around either. His shorts went down to about here [points to the mid-thigh area].

And I did have my shoes. I just couldn’t walk over those rocks. Every place you surf, if it’s a good surfing spot, has rocks. Even out in front of our house—at Mary’s—there were rocks. When there was a lot of sand, it seemed like the surf was no good. And Rincon has rocks everywhere. When I had gone to Hawaii [in 1953], I had bought these shoes [two-toe Japanese shoes] and Bob glued the rubber to the bottom. They worked great.

Women surfers…

In those days, there weren’t too many other women surfing. There was one who came up from down south, Marge Calhoun. She started surfing a few years before me. She was a really good surfer. She was a big tall gal. She had the knack for it, and won a championship in Hawaii. Later there was a girl named Phil, she surfed California Street, then Rincon. And once she came out to our place. Phil started surfing, oh, maybe two or three years after I did, and she married a surfer. They started having kids. I remember she would surf pregnant. It really bugged everyone because they would all have to get out of her way, because she was pregnant. I thought that was kind of stupid, but she surfed until she was about seven months—she was pushed way out, her belly that is.

You gotta remember, when I started surfing, there wasn’t a lot of younger kids around to give us a hard time because we were women. Everyone we knew was in junior college or college or older. And everyone here in Ventura was fairly chummy. We didn’t have too much “riff-raff.” Everyone that surfed at California Street was mostly from Ventura, the ones at County Line [Rincon] were from Ventura, or we knew them. They were always very nice to me. I’ll never forget that when I would catch a real good ride, the guys would tell me it was good. And they’d tell me what I was doing wrong. I don’t remember anyone ever trying to wipe me out or anything…I think because I was much older. Of course, there were the Malibu rats, who were pretty young. The Malibu rats were the only ones that gave me a rad time when they were at Rincon, ‘cause I only surfed Malibu once, but they came up to County Line [Rincon] quite a bit.

I went up to Rincon lots of times by myself. I wouldn’t surf by myself a lot at Mary’s because it upset my mother so much, unless someone else was in the water. My mom didn’t like me to be out there alone. But they again it was sort of a rule that we didn’t surf a lot alone. But I would drive up to Rincon by myself all the time.

The surfing life…

We had an old ’47 Buick that Bob had a wreck in. After the wreck, the fender wasn’t any good, so he pulled it off and built a rack for three surfboards, one, two and three—Bob, Larry and Mary. They stuck out quite a ways, so we had to put a red flag on the tail. That was our first surfing car. We could drive all around, down south, Rincon, Mando’s—and don’t forget California Street, I surfed there a lot too. When we went surfing, we were always gone until dark, it was always an all-dayevent, especially on the weekends.

Nobody else had a car like the Buick. After the Buick conked out, we had a Mercury, and we’d just put the boards on top with racks.

Once we went up to Kenny Kessin’s house [at Rincon], and he had a “noon hour,” or whatever he called it. It was at night and everyone was dress, y’know, Hawaiian style. I don’t remember what I wore, because I didn’t have any Hawaiian stuff, maybe I had a muumuu. It was a nice party, but to tell you the truth, I was bored because everyone was getting drunk. You see, we didn’t drink and so many others did. I drank when I was younger, but you have to remember I was older than most everyone at this time. Sometimes I felt out of place at those get-together-type things.

I remember going to see Bud Browne’s film in Santa Barbara. Everyone and their brother was there. Everyone that we knew. Phil was there, Jack was there, everybody. It was a real big event. They had it in some auditorium, or something like that. It was very upbeat, not too rowdy, not a lot of monsters, like they have now. Surfing was still pretty quiet then, that is until after Gidget.

The Pitas Point surfing club…

Well, there were these kids that were from the San Fernando Valley, they formed a club and would come up here and surf. Now, they couldn’t come in and surf Mary’s because the property was private. They went up to the County Park—which was legal—and hobbled over the rocks to get down to Mary’s, and I just made friends with them because they were all such nice kids. It was an informal club… but that’s what they named themselves, The Pitas Point Surfing Club, because that is Pitas Point up there.

Other surf spots…

I never surfed the Oil Piers, or Stanley’s or any “straight in” beach. I surfed Rincon lots and lots and lots! I ate at Stanley’s a few times, but never surfed there before. There were other placed to surf, y’know. I went to San Onofre once. We just spent the day there. And then surfed Tresles. Boy did we luck it. It was a six-foot day, and it was great!

I surfed The Tanks once and did all lefts. I was so proud of myself because I wasn’t into lefts much. It was a short wave, but a fast one. I really had a ball!

But oh, Secos [Arroyo Sequit, Leo Carrillo State Park] I really caught a beautiful ride there! We called it “The Rock,” too. It’s in Ventura County, I think, just on the other side of the County Line [on the other side of County Line], near that Carrillo beach business. We’d go there quite a bit. The guys and girls would all go down there. The girls would lay on the beach—except for me. The guy’s girls didn’t mind me surfing. You see I was older, so I wasn’t any competition for them.

I once remember one time Secos was so good. The waves were huge! All these kids wouldn’t surf, it was too big, they said. Maybe nine feet or higher. But I surfed, and went all the way to the shore, and Mickey Chapin, he went by that name first and then changed it to Mickey Dora, came up to me and said, “That was a nice ride.” I remember that. He was a good guy. And Mike Doyle, too, was always so nice to me.

Best surfs…

It was Rincon where I caught my all-time greatest wave on my little splinter. Kenny Kessin said it was definitely fifteen feet. It was New Year’s Day. I remember Jack Cantrell got there late. It was great surf, but they the wind came up and he missed all the great surf, because then it blows out, it blows out! But the wave I caught was fifteen feet! It was great!

One day at Rincon, Jack and I were surfing, and the waves were just great, about eight feet. And Jack was helping me with my surfing, giving me lessons. Waves would come and he’d holler, “No, no, no!” But everytime, I thought he was saying, “Go, go, go!” Well, due to that I had the best surfing day of my life that day. He thought the waves were going to ruin me, but it was a great day!

Final thoughts…

Why surfing? It was mainly the thrill of it all. It is so exciting. Here you are, high as a ceiling, and then “sshrooom!” And sometimes you make it and sometimes you don’t. I swam in more than anybody in the state. I’d get wiped out, lose my board, swim in, get it, and paddle back out. I loved it!

Monks died at the age of 89, a legend in local surfing folklore — a first female surfer and her favorite surf break was named after her.